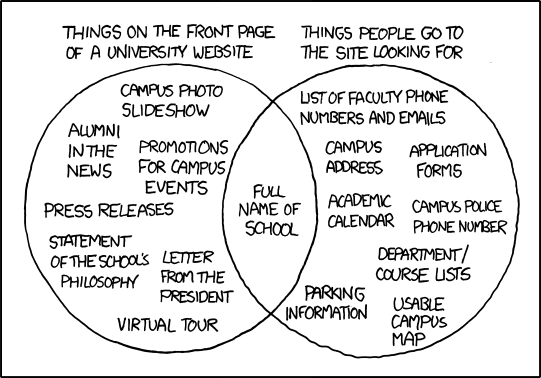

From the always-on-pitch xkcd.

Presented without further comment.

"as if the world weren't full enough of history without inventing more." ~ granny weatherwax, wyrd sisters.

there is this weird thing in western culture, especially n american culture, where people/adults seem to believe that they have a right to discriminate against children.

recently, i was hanging out at a bar, when a friend called and invited me to come hang out for a few drinks and chill time as the sun came up. cool. then, i heard a bit of whispers in the background and the question posed to me: is aza with you?

ummm…what? why? does that matter? ...

im not a feminist ( yeah, i said it...shrug). but i dont understand people who claim to be feminist on one hand, and on the other hand think that children should be designated to certain public and private spaces, not mixing in ‘normal’ public areas, such as restaurants, stores, airplanes, etc. cause in us culture, when you create little reservations for children, you are really creating little reservations for mothers. it is the mother who will be sent away to take care of the child. and how is that supporting all women and girls?

There is a conversation that needs to happen, where we discuss how children are part of our society, how they have a right to exist, to take up space. How we are here to protect them and teach them to exist in the adult world because they don't yet understand how to navigate our world alone. But we can't really have that conversation, because every time we do, someone has to assert that children just should not be in certain places because children infringe on their rights, ignoring the rights children should have, but don't.

To demonstrate this, take a look at the wonderful post written by maia at Feministe about how to support parents in public spaces, and the 400+ (at the time of this writing) comments in it that have burst forth with numerous remarks about how children are unholy terrors in restaurants and ruining things for everyone else.

I am collecting women’s accounts of the physical experience their orgasms. I’m really hoping that some of you can help me out with this. Feel free to pass it on to any women or lists with women who might be interested.

Details –

I am seeking first person descriptions from women about their orgasms.

Who: You are a woman, 18 years or older, who have experienced one or more variety of orgasms. (Transwomen! I want your unique perspectives too!)

What: Essay of clear and detailed description of your orgasm, from start to finish, focusing on the physical experience, expressed in your own words. When does it start? What’s the hint of it? Where does it start? How does it move through your body? What sort of sensations? Imagine trying to illustrate your orgasm to a person who’s never had it.

If you have more than one type of orgasm, each variety would be written in a separate essay piece. (The get-to-sleep quickie, the deep one, the surprise one, the long building one, solo-sex one, when getting oral sex, etc…)

How Long? As long as it takes for you to describe it. It may be a couple of paragraphs or couple of pages.

Credit line: How would you like your essay to be credited? You’ll have one or two lines.

Editing: At most I will edit for grammar, spelling and simple readability. I want to keep it as true to your original narrative and tone as possible.

When: No later than end of August

Send to midori AT fhp-inc DOT com

Please make sure that there’s an e mail I can reliable reach you at. I may have some questions around editing or some other detail.

I’m happy to answer any questions on this.

Thank you!

Midori

A few weeks ago, when I was in Maine for the weekend I found time to read Alison Oram's slim little volume on gender crossing in mid-twentieth century England (1920-1960s, roughly), as reported in the popular press. Her Husband Was a Woman!: Women's gender crossing in modern British pop culture (New York: Routledge, 2007) explores how gender identity and sexual orientation was understood -- or at least reported -- in tabloid newspapers, and how it changed over time from the dawn of the twentieth century to the postwar era.

A few weeks ago, when I was in Maine for the weekend I found time to read Alison Oram's slim little volume on gender crossing in mid-twentieth century England (1920-1960s, roughly), as reported in the popular press. Her Husband Was a Woman!: Women's gender crossing in modern British pop culture (New York: Routledge, 2007) explores how gender identity and sexual orientation was understood -- or at least reported -- in tabloid newspapers, and how it changed over time from the dawn of the twentieth century to the postwar era.  My friend Joseph, who blogs over at Greensparrow Gardens, was on the NPR show Splendid Table this weekend, talking about his new tomato hybrid (final segment). Annie Lamott once said in a talk I attended that in her family, making it onto National Public Radio was the sign that someone had Made It as a writer, artist, thinker, etc. And I've always thought that was a pretty good litmus test (as frightfully liberal bourgeois as that might make me sound!). So congrats, Joseph, and hope this is only the first of many appearances. My vote? Shoot for This American Life or Fresh Air next!

My friend Joseph, who blogs over at Greensparrow Gardens, was on the NPR show Splendid Table this weekend, talking about his new tomato hybrid (final segment). Annie Lamott once said in a talk I attended that in her family, making it onto National Public Radio was the sign that someone had Made It as a writer, artist, thinker, etc. And I've always thought that was a pretty good litmus test (as frightfully liberal bourgeois as that might make me sound!). So congrats, Joseph, and hope this is only the first of many appearances. My vote? Shoot for This American Life or Fresh Air next!

Danika @ The Lesbrary has a fun post up sharing notes from a conversation between herself and a friend Cass about Radclyffe Hall's The Well of Loneliness (1928).

Danika @ The Lesbrary has a fun post up sharing notes from a conversation between herself and a friend Cass about Radclyffe Hall's The Well of Loneliness (1928). C[ass]: The term ‘homosexuality,’ while in use in 1928, didn’t yet have its modern definition or its now understood division from gender. Inversion, on the other hand, completly tied sexual orientation to one’s gender and gender expression. A person labelled female at birth could not, by defition, be an invert without displaying masculine traits and masculine leanings. Therefore, in order to be a novel ABOUT inversion, Stephen has to be masculine. If we are using our modern lens here, then we can agree that, despite her masculinity, Stephen is not automatically male. The fact that her parents gave her a traditionally male name is out of her control. Lots of girls who continue to identify as women like to dress in pants rather than dresses because they are easier to walk and play in. Looking “like a man” or being masculine doesn’t make a person a man.

The conversation with her father is trickier, but if she has a crush on a girl, and thinks that only men and women can have relationships together, it’s logical that she would want to be a man in order to be happily in love with a woman.

D[anika]: True, but coming from a modern perspective, that assumes that you are by default the gender you were assigned at birth and only the opposite if there is overwhelming evidence. We don’t have overwhelming evidence that Stephen would identify as a man, but we have a lot less evidence than there is for Stephen identifying as a woman. She can’t stand to even be around women, except the ones she falls in love with.

That makes sense, but it isn’t just around having a partner that Stephen is frustrated at being labelled a girl. In fact, as some point she said “Being a girl ruins everything” (not an exact quote)

C: [...] [H]er gender and gender expression can be on the trans-masculine spectrum without her necessarily being trans. In 1928(ish), being a girl DID ruin everything!

I think you are the gender you understand yourself to be, but sadly I can’t ask Stephen. ;)

I wrote this in a bathroom at a cafe a week ago on a chalkboard (meant for customer use).

![My sister is bisexual. I come from a tiny town that hates homosexuality. THANK YOU, Austin for accepting all people [heart] MRC.](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh1riFVyN_Zt3cvEer_JwnWI2coEwsAT6OsyWyNQFyabh8TfhOSc8dAMVKKcYFlWeURC65vmYXTRkSCw2GnEGd5qPPFbsYmmM_6TnFacNPT6AdDIt9mM_ZAEfvBvnT4jOAjmN8-snvjAuo/s400/homophobes.JPG)

Today, I went back. Under is someone wrote, "well, we don't really support homophobes, so you're welcome."

I thought that was a grand response.

In 2006, she completed a Ph.D. in Health Behavior with a concentration in Human Sexuality. She also holds a MS in Counseling Psychology and a BA in Psychology with minors in Cognitive Science and Philosophy. She’s worked for well over a decade in the field of sexuality education and has grown into an impassioned advocate for social justice through sexual fulfillment. Politically progressive and unapologetically atheistic, Emily has strong opinions and a big vocabulary, and she’s determined to use both to make the world a better place for human sexual expression.

So look, I’m going to say this thing, and you’re going to listen and believe me because… I don’t know, why would you believe me if you haven’t believed it from anyone else? Because I’m clever and have a PhD and things? No, you’ll believe me because it’s just true. Because in the patient corners of your heart, you’ve ALWAYS known it’s true. It’s this:

You’re not broken. You are whole. And there is hope.

You might be stuck. You might be exhausted. You might be depressed, anxious, worn out by the demands your caring makes on you, and in desperate, dire need of renewal. You might be tired of feeling like you need to defend yourself. You might wish that, just for a little while, someone else would defend you and protect you so that you could lower your guard and just be. Just for a while.

Those are circumstances, they’re not YOU. YOU are okay. You are whole. There exists inside you a sexuality that protects you by withdrawing until times are propitious.

I completely get how terribly frustrating it can be that your partner’s body feels like times are propitious right now, while your body is still wary. And it’s even worse because the more ready your partner’s body seems, the more wary your body becomes. It is The Suck, Like Woah, for both of you.

But it’s in there, your sexuality. It’s part of you, as much as your skin and your heartbeat and your vocabulary. It’s there. It’s waiting. You’re okay. Just because you’ve had no call to use the word “calefacient” or “perfervid” lately doesn’t mean it’s not longer available to you. Should the opportunity arise, there it will be, ready, waiting. Like the fire brigade. Like a best friend.

There’s a bunch of stuff you can try to create propitious circumstances.

Now imagine you’re a person who’s always identified as straight and then you come to college and you meet this amazing person who happens to be the same gender and you just fall head over heels, even though you never even imagined being in a same-sex relationship before… are your feelings less genuine simply because they might not have occurred in a less inclusive environment?

Should you choose NOT to get into a relationship this person you’re attracted to, on the grounds that you might not be attracted to that person under other circumstances?

Is the only REAL love a love that would thrive even in a hostile, hateful landscape? Only if you can love through being egged and threatened on the street is your love real?

That’s not the standard we set for straight relationships or relationships that look heteronormative.

I can totally see where the resentment would come from, and yet… I can’t bring myself to judge a person’s individual, internal, emotional experience on the basis of its political import. How could *I* know whether or not someone really loves someone else? Can I tell from the outside whether she’s a “real lesbian” or “just experimenting?” If it not my relationship, is it any of my business?

With so many barriers lowered these days, it’s hard to generate compelling and original reasons for your hero and heroine NOT to get together. I think sci fi romance, vamp stories, werewolf stories, shapeshifter stories are so popular because you can invent all kinds of rules about how risky it is for a human to mate with a whatever or who knows. And historicals, where you can use the rules of society that USED to keep people apart but don’t anymore.

Dorothy Sayers needed three novels – two of them VERY long – to disentangle her hero and heroine from their stigma. He saved her life; it’s a problem. 5 years later he allowed her to risk it, thus giving her life back to her. Her “Greater Than Themselves”? Detection, murder investigations and, under that, the truth at all costs. Her big “They Know” scene takes place in a punt on the Isis in Oxford, where they both went to school and which represents intellectual refuge from the discord and bitterness of the human world.

Me, I like writing Reunited Lovers stories because the stigma is built in: one of them done the other one wrong, enough that they split up. How are they ever going to fix it? But whatever brought them together in the first place makes a perfect Greater Than Themselves.

So now you know the trick to falling in love if you’re fictional.

LC Control Number: n 80104485

HEADING: Cook, James I., 1925-

Biographical/Historical Note: b. Mar. 8; Th.D. from Princeton; prof. of Biblical languages & lit. at Western Theol. Sem.

Found In:Grace upon grace ... 1975.

Has there ever been a franchise whose fan base has been so maligned? It's starting to feel like some of the male critics of Twilight are just uneasy that, for once, something that isn't aimed at them is getting such a big slice of the zeitgeist.

Meanwhile, instead of defending the film, some feminists aren't happy either because of Bella's passivity and the tale's theme of abstinence before marriage. Well, OK, author Stephanie Meyer's devout Mormonism does give weight to that reading of the text. But it's not really as simple as that. We can presume a lot about the author's intent, but that's not necessarily the message the films' fans are taking away from it.

In my interviews and survey of 3,000 fans, the majority express sometimes contradictory beliefs in the supernatural while asserting adherence to traditional religious institutions. Yet, while Twilight won’t replace organized religion, it reflects a longing for sacred and extraordinary experiences in everyday life that are perhaps missing in traditional religious venues. In pilgrimages to Forks, Washington, the setting for the books (in July 2009 alone, 16,000 fans trekked to Forks like supplicants at a holy site, more than the total number of visitors in 2008), fans indulge the fantasy that a supernatural world exists alongside our own, searching for vampires in the woods and lingering outside the re-imagined home of Bella. Rather than fueling interest in vampirism, a concern among some Christian critics of the books, the series provides what Laderman calls “myths that provide profound and practical fulfillment in a chaotic and unfulfilling world.” It’s also impossible to separate these moments of spiritual enchantment from the Twilight franchise, which ceaselessly offers consumption to women and girls as a way to retain the feelings of belonging, romance and enchantment. There are Edward and Bella Barbie dolls, lip venom, calendars, video games, graphic novels, and fangs cleverly promoted and eagerly purchased at conventions and online stores. Yet, the shrines attest to the way fans also transform these objects into something personally vital within the messy entanglements of commerce and enchantment.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Reading a book, losing oneself in the imagination of an author is usually a solitary enterprise. So, too, is writing a book, says author Neil Gaiman.

NEIL GAIMAN: Writing is like death, a very lonely business. You do it on your own. Somebody is always sitting there figuring things out. Somebody is always going to have to take readers somewhere they have never been before.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But, as books move from printed page to networked screen, it grows easier for writers and readers to gather in the virtual margins to discuss the plot and characters and for readers to actually help shape them.

Crowd sourcing artistic expression in this way may seem contrary to the rules of creativity - books by committee? But Bob Stein, founder of the Institute for the Future of the Book, sees an inevitable merging of writer and reader.

As someone who for decades has experimented with new forms for books, he’s used to people who grew up with traditional books reflexively rejecting his ideas, as when he explained his vision to a group of biographers.

BOB STEIN: One of the people in the room was one of these writers who gets a two-million-dollar advance, goes away for ten years, literally, writes a book, sells a lot of copies and then does it all over again. So I said to him, instead of getting your two-million-dollar advance and going away for ten years, how about if your publisher announced to the world so-and-so is going to start work on a biography of Barack Obama, who’s interested?

And n-thousands of people say, yes, I'm interested, and they subscribe to your project and they pay two dollars a year, whatever it is. I said, at the end of ten years you'll have a body of work, and you'll have the same two million dollars.

The difference will be that you've done this in public and you've done this with a group of people helping you in various ways.

And he, of course, as I expected, you know, put his fingers up in a cross, saying, oh, my God, that’s the most horrible thing I've ever heard of, that’s the last thing I ever want to do.

And I said to him, I'm willing to bet you that there’s a young woman who’s getting her PhD right now who grew up in MySpace, in Facebook, somebody who is comfortable and excited about working in a public collaborative space. She is a seed of the future.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But how do you make money in your vision, the subscription model?

BOB STEIN: It’s all subscription. The day that the

author is no longer interested, and she doesn't want to work with the readers any longer, she stops getting royalties.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You know, there are many authors who talk about a quiet place, a moment of inspiration, alone.

BOB STEIN: It’s very interesting. The very concept of an author, the very idea that somebody owned an idea, is extremely recent. Remix culture, you know, where something is constructed from lots of different parts, remix culture was actually the standard until print came along. Print actually changed everything because suddenly you weren't relying on -

BROOKE GLADSTONE: An oral tradition.

BOB STEIN: - on the oral tradition.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I'm simply raising the fact that whether or not the author holding up his hands in a get-thee-from-me-Satan position is a biographer or a philosopher or a novelist, there’s not necessarily a role, at least in the beginning of creation, for the reader.

BOB STEIN: I – we're, we’re definitely in a space where it’s almost impossible to argue about this.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Because you’re projecting into a future where that quiet place will no longer be necessary?

BOB STEIN: [SIGHS] Basically, yeah.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What about the thingness of books?

BOB STEIN: I'll miss it. I love holding the object in my hand. On the other hand, when I'm online and suddenly my daughter, who lives in London, shows up in the margin of something we're reading together, chills go up and down my spine. Being able to share an experience of reading with people whose judgment I care about is deeply rewarding.

Here’s a wonderful sort of factoid which may be helpful: The western version of the printing press is invented in 1454. It takes 50 years for page numbers to emerge. It took humans that long to figure out that it might be useful to put numbers onto the pages.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

We're at the very, very beginning of the shift from the book to whatever is going to become more important than it. I realize that there’s a way to see what I'm saying and, and sort of say, there is a truly mad man, and, and in a lot of ways I, I can't prove it, but – you, you understand the problem.

"I Love My Children. I Hate My Life." That's the cover line on this week's New York magazine, superimposed on a photo of a beautiful mother and infant in a sun-drenched landscape. Presumably, the mother is loving her child and hating her life. Presumably, we all are.

If you're having a baby for reasons of self-gratification, of course you're going to be miserable. Becoming a parent is less about enriching your life than it is about up-ending it entirely to make room for another human being. And that's what Senior's article is missing: the fact that children are people, and having a child is about forging a relationship. Take this quote from a sociologist Senior interviewed about why parents are so disgruntled: "Middle-class parents spend much more time talking to children, answering questions with questions, and treating each child's thought as a special contribution. And this is very tiring work." Funny, that doesn't sound like work; that sounds like having a conversation. The true reward of parenting isn't looking back with nostalgia, as Senior concludes; it's getting to watch a baby turn into a fully realized person. It's hearing the thoughts and opinions of somebody who didn't exist until you brought them into the world. It's a humbling, daunting, awesome experience -- and it's hard enough without the added pressure of making every moment enriching and significant.

Middle-class couples spend much more time talking to each other, answering questions with questions, and treating each other's thoughts as a special contributions. And this is very tiring work.

From Amanda Marcotte @ RhReality Check comes a wonderful interview with Amber Kinser, author of a new book, Motherhood and Feminism (Seal Press, 2010). The following passage, while focused specifically on mothers in the workplace, speaks to a lot of the issues I was blogging about in my recent post on feeling guilty for wanting a balanced life (starts at roughly minute 19:00).

From Amanda Marcotte @ RhReality Check comes a wonderful interview with Amber Kinser, author of a new book, Motherhood and Feminism (Seal Press, 2010). The following passage, while focused specifically on mothers in the workplace, speaks to a lot of the issues I was blogging about in my recent post on feeling guilty for wanting a balanced life (starts at roughly minute 19:00). There is an assumption in the workplace that if you're a mother your primary loyalty is always going to be your family even during the workday and that that's a problem. The assumption is, for men, your primary loyalty is always going to be at the workplace and that that's not a problem. And if you're single and you're ... childfree and female then we don't have to worry that you'll be called away, you know, to go pick up a child who's sick from school or go take care of a disciplinary matter or go the Halloween parade at school.

So part of the problem [of discrimination against mothers in the workforce] is this mythical -- and I talk about this in the book a good bit -- this mythical split between public and private. The workforce still operates on the assumption that home life is separate from work life. It never has been, it isn't now, and it never will be. And so part of the problem is the problematizing of people who are invested in their families. So that if someone has to go to the piano recital during the school day or someone has to go take care of a sick child this goes up against workplace policy and norms. And so what we do is penalize -- largely the women, because they're the ones who end up doing it -- who do that. That's where that motherhood penalty comes in -- instead of shifting workplace norms so that they can accommodate the fact that public life and private life are not, you know, they're just not distinguishable. Men are better positioned to be able to pretend like they're separate than women are and so they benefit in the workplace.

On Tuesday, I posted a quote from Terry Eagleton's On Evil. To risk appearing completely enthralled by Eagleton's prose (which I admit are difficult not to delight in), today I'm sharing a passage from Holy Terror (Oxford: Oxford U.P., 2005), which Hanna recently finished and handed off to me.

On Tuesday, I posted a quote from Terry Eagleton's On Evil. To risk appearing completely enthralled by Eagleton's prose (which I admit are difficult not to delight in), today I'm sharing a passage from Holy Terror (Oxford: Oxford U.P., 2005), which Hanna recently finished and handed off to me. Dionysus [in Euripides' play The Baccae] offers men and women precious time off from their burdensome existence under the political law. We have seen already that such carnivalisque interludes are in the interests of the governing powers rather than an affort to them. As Olivia observes in Twelfth Night, there is no slander in an allowed Fool, no harm in jesters so long as they are licensed. When transgression is ordained, deviancy becomes the norm and the demonic finds itself redundant. This is why the devil finds himself with empty hands in the postmodern world. If Jesus's law is light, however, it is not only because he, too, comes to relieve the labouring poor of their afflictions, but because God commands nothing more of his people than that they should allow him to love them.* Because he is the Other who neither lacks nor desires, unlike the Lacanian variety, he needs nothing from others, and his law is consequently free of neurotic compulsion and paranoid possessiveness. Ironically, it is God's transcendence -- the fact that he [sic] is complete in himself, has no need of the world, and created it out of love rather than need -- that allows him to go so easy on his creatures.

God himself has the necessity of law, in that his being is not contingent. But this law, once again, is the law of love -- for since nothing apart from God needs to exist, whatever does exist does so gratuitously, as a result of his unmotivated generousity. To say that things were created out of nothing means that they did not have to come about. The did not follow inexorably from some precedent, as elements of a causal or logical chain. Creation, in Alain Badiou's terms, is an "event," not a dreary necessity. The cosmos could quite easily never have happened. Instead, God could have devoted his considerable talents to, say, figuring out how to create square circles ...

... Since religious fundamentalism is among other things an inability to accept contingency, the universe itself is a persuasive argument against such a creed. What fundamentalism finds hard to stomach is that nothing whatsoever needs to exist, least of all ourselves. For St Augustine, the fact that human beings are "created" means their being is shot through with non-being. Like modernist works of art, we are riddled from end to end with the scandal of our own non-necessity (p. 32-33).

One of our post-graduation presents for Hanna, one which I also get to enjoy the benefits of, was a subscription to the London Review of Books. The most recent issue includes a review of Christopher Hitchin's latest book, Hitch 22, a memoir. Hitchins, like other public personalities who trade in sensationalism and putting other people down, is easy to dislike for his self-absorption and snobbery. When the memoir first came out, John Crace @ The Guardian crafted a "digested read" version that played on this propensity and had Hanna and I falling off our chairs with mirth.

One of our post-graduation presents for Hanna, one which I also get to enjoy the benefits of, was a subscription to the London Review of Books. The most recent issue includes a review of Christopher Hitchin's latest book, Hitch 22, a memoir. Hitchins, like other public personalities who trade in sensationalism and putting other people down, is easy to dislike for his self-absorption and snobbery. When the memoir first came out, John Crace @ The Guardian crafted a "digested read" version that played on this propensity and had Hanna and I falling off our chairs with mirth. I find I have written nothing of my wives, save that they are fortunate to have been married to me, and nothing of my emotional life. That is because I don't have one. The only feeling I have is of being right, and that has been with me all my life. I would also like to point out that drinking half a bottle of scotch and a bottle of wine a day does not make me an alcoholic. I drink to make other people seem less tedious; something you might consider when reading this.

For Schmitt, political romantics are driven not by the quest for pseudo-religious certainty, but by the search for excitement, for the romance of what he calls "the occasion". They want something, anything, to happen, so that they can feel themselves to be at the heart of things.

It certainly sounds like it has all been a lot of fun. His has been an enviable life: not just all the drink and the sex and the travel and the comradeship and the minor fame (surely the preferable kind), but also the endless round of excitements and controversies, the feuding and falling-out and grudge-bearing and score-settling, the chat-show put-downs, the dinner party walk-outs, the stand-up rows. Christopher Hitchens has clearly had a great time being Christopher Hitchens. But – and I don’t want to sound too po-faced about this – should anyone’s life be quite so much fun, especially when it is meant to be a kind of political life? Hitchens admits to some regrets, including that he has not been a better father to his children (and by implication a better husband to his wives, though he doesn’t actually say that), but he doesn’t seem to have agonised about it much. In fact, he doesn’t seem to have agonised much about anything. He doesn’t rationalise his political shifts so much as acquiesce in them: if it feels like he has no choice, then he has no choice but to follow his feelings. He has seen his fair share of misery and despair, and may have caused a certain amount of it himself, but it is entirely unclear what this has cost him.