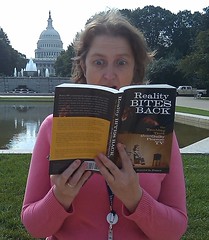

I have to begin this review with a disclaimer: I have virtually no first-hand experience with the type of reality television discussed in Jennifer Pozner's Reality Bites Back: The Troubling Truth about Guilty Pleasure TV. This has been through both accident and purposeful avoidance. On the accident side, I didn't grow up with a lot of television around, and (The West Wing aside) TV has never been a very social experience for me. Therefore my exposure to it has been primarily through advertisements, grocery-store checkout magazine headlines, second-hand reports and cultural analysis.

I have to begin this review with a disclaimer: I have virtually no first-hand experience with the type of reality television discussed in Jennifer Pozner's Reality Bites Back: The Troubling Truth about Guilty Pleasure TV. This has been through both accident and purposeful avoidance. On the accident side, I didn't grow up with a lot of television around, and (The West Wing aside) TV has never been a very social experience for me. Therefore my exposure to it has been primarily through advertisements, grocery-store checkout magazine headlines, second-hand reports and cultural analysis.Why have I avoided reality television? My parents can tell you that public humiliation and social deception has always made me acutely uncomfortable: when we used to watch romantic comedies when I was younger, plot elements that revolved around social lies (Roxanne, The Truth About Cats and Dogs) -- no matter how benign and ultimately happy-ending they turned out to be -- sent me running to the other room in discomfort. I didn't like the idea of even a fictional character's emotional manipulation. So the prospect of watching any show that was actually constructed around such false social interactions involving real people had zero appeal. Add to that formula the heteronormative gender roles that are portrayed and reinforced in these shows, and my personal anti-manipulation bias was bolstered by political critique.

This is all to say that when Seal press sent me an advance review copy of Reality Bites Back last week I had a lot of pre-formed cultural skepticism and personal discomfort concerning the premise of reality television. And I imagine this book struck me differently than it would a devotee of American Idol or The Amazing Race or come across to those of you who remember watching (for example) the first season of Survivor or The Bachelor with your buddies in high school or roommates in college.

Jennifer Pozner is a media critic and educator specializing in media literacy. She is the founder and executive director of Women in Media & News, which promotes the increased participation of women in media creation and analysis. Thus, Reality Bites Back is the work of someone who is deeply immersed in media as a creator of content, a passionate consumer, and an astute critic of the ways in which media inform our political and personal lives -- on both a conscious and subconscious level. In her introduction, Pozner describes the decline in media literacy and critical analysis around reality television shows that she has over the past decade, as she tours college campuses and speaks about the messages that reality television sends to viewers. While students in the early 2000s were critically aware of the constructed nature of reality programming -- a phenomenon that had only recently been widely adopted by the big networks and was getting a lot of press -- young people today have grown up with much more of the genre in their media diet and (Pozner argues) their "critical responses to gendered, raced messages within media 'texts' ... seems to have suffered as a result" (30). "The Millennial Generation," she writes, "seems to be getting more cynical ('Of course it's all bullshit, but it's funny. Whatever.') but less skeptical. This kind of mind-set makes advertisers salivate" (31).

The goal of Reality Bites Back is, in part, to re-energize the critical faculties of reality television viewers, so that they become less susceptible to the poisonous narratives of gender, sexuality, race, and class that reality television producers are peddling. Pozner reminds us that reality television producers -- far from neutrally capturing how people interact with one another -- aggressively shape the stories that are told on-screen about how human beings behave. And these stories reinforce what we already "know" about women, men, heterosexuals, queer folks, people of color, poor people, rich people, and so forth. They are brain candy in part because they tell us familiar stories about the world, rather than challenging our pre-conceptions about how folks behave. Stories like:

- Romance and love is exclusively the province of white heterosexuals.

- Romance and love are signified by providing (if you're a man) and consuming (if you're a woman) brand-name products.

- Single women, no matter their social and financial circumstances, are desperate for male validation and will quit their jobs, submit to public humiliation, and accept the attentions of any man they are presented with.

- Single, married, with or without children, women are seen as selfish, controlling, untrustworthy, desperate, pathetic individuals whose only worth is derived from their ability to meet draconian expectations of physical perfection and sexual availability.

- Men must be rich in order to be eligible for (hetero) relationships, and their wealth is the only thing that matters: criminal records, histories of domestic abuse, on-screen abuse of female cast members are rewarded.

- Men who treat women contestants as independent persons worthy of actual human-to-human interaction are rebuked by on-screen experts.

- Poverty is an individual, not a structural problem, best alleviated through on-screen charity and gifts of various brand-name products.

Above all, Pozner argues, reality television programs are hour-long product placement advertisements, their primary raison d'etre being the income generated by advertiser revenue. These shows are indeed market-generated, as producers would have us believe -- but the "market" is not the audience who tune in to the programs, but the advertisers who pay to have their products relentlessly shilled in situations that viewers do not read as advertisements. These programs -- like most advertisements -- contain the not-so-sub subtext that the best way to achieve the good life in America today (understood in the context of reality television a life of wealthy, socially conservative conformity) is by maxing out your credit card and purchasing it.

As an historian, I feel compelled to point out that this permicious blend of consumerism, competition, and capitalizing on economic and social desperation is hardly new. It's not really within the scope of the book Pozner set out to write to provide historical analysis, so I don't think the book is remiss in not providing it. Nontheless, I found myself thinking of potential historical comparisons and desiring some sort of historically-situated analysis that looked beyond anti-feminist backlash, media mergers, and the current recession.

One comparison that comes to mind, for example, are the Depression-era dance marathons, in which desperate couples vied for prize-money while contest sponsors walked away with the cash. As the entry at HistoryLink explains

One comparison that comes to mind, for example, are the Depression-era dance marathons, in which desperate couples vied for prize-money while contest sponsors walked away with the cash. As the entry at HistoryLink explainsDance marathons opened with as great a fanfare as the promoter’s press agents could muster. Each major promoter had a stable of dancers (known as horses, since they could last the distance) he could count on to carry his event. These professionals (often out-of-work vaudevillians who could sing and banter and thus provide the evening entertainment that was a feature of most marathons) traveled at the promoter’s expense and were "in" on the performative nature of the contests (including the fact that the outcomes were usually manipulated or at least loosely fixed).You can read the whole article over at HistoryLink.org.

Known euphemistically as “experienced couples” (The Billboard, April 14, 1934, p. 43), professionals did their best to blend in with the hopeful (often desperate) amateurs. For all contestants, participation in a dance marathon meant a roof over their heads and plentiful food, both scarce during the 1930s. President Herbert Hoover's promised prosperity "just around the corner" eluded most Americans, but dance marathon contestants hung their hopes on the prize money lurking at the end of the contest's final grind.

...Medical services were available to contestants, usually within full view of the audience. Physicians tended blisters, deloused dancers, disqualified and treated any collapsed dancer, tended sprains, and so on. "Cot Nights," in which the beds from the rest areas were pulled out into public view so the audience could watch the contestants even during their brief private moments, were also popular. The more a marathon special event allowed the audience to penetrate the contestants’ emotional experience, the larger crowd it attracted.

The heady mix of consumerism, voyeurism and exploitation, in other words, is not unique to our era, nor is it an invention of reality television creators. However, the fact that exploitation and backlash is unoriginal hardly exempts it from critical analysis -- just like the fact that a show is being sold as fluffy, lighthearted "fun" escapism doesn't mean with should turn off our critical filters.

The tie-in website for the book, RealityBitesBackBook.com, contains links to a whole series of essays and excerpts if you're interested in checking Pozner's work out in more detail before trotting over to your library and/or bookstore of choice and obtaining a copy to read in full.

What a great review! I will most definitely pick up a copy to read myself.

ReplyDeleteThe point about reality t.v. reinforcing the "Poverty is an individual, not a structural problem, best alleviated through on-screen charity and gifts of various brand-name products," narrative particularly resonates with me.

I, too, avoid most t.v. in general, largely from not wanting to pay for cable... but the media/entertainment industry is so pervasive and has more impact on my daily life than I realize, I imagine, even without the television.

Thanks for this post!