|

Molly Haskell at a book signing for

My Brother, My Sister (via) |

Just before leaving on vacation, I was asked to review the new memoir

My Brother, My Sister: A Story of Transformation by Molly Haskell (Houghton Mifflin, 2013). I spent the flight from Boston to PDX reading ... and taking increasingly irritated notes. While I didn't actively seek out this book to review, I had slightly higher hopes for a memoir that promised in its ad copy to be a "candid" and self-critical memoir by a "feminist academic" who not only seeks to describe her own journey to understanding but also to "chart the cultural map ... of gender roles and transsexualism." I had hopes for a memoir that evidenced both better understanding of the trans issues its author attempts to outline for readers -- one that hadn't fallen into some of the most basic traps of our problematic cultural narratives about trans lives.

Part of my disappointment comes from the fact that cis* family members and friends of trans individuals often struggle to get up to speed on trans issues after a loved one opens up about their experience -- and there is a need for personal narratives by individuals who have struggled through ignorance and misconception into better understanding. Such stories don't need to paper over the messy reality of feeling that often accompanies such a journey. I have a friend whose spouse came to the realization of their transness within the last two years, and as a partner my friend struggled with many of the same feelings a major life change will bring: grief over the loss of "before," fear about what the future will bring, uncertainty about what this change meant for their relationship and family life, sometimes anger at their spouse for being at the epicenter of this upheaval -- and for mostly not sharing in the grieving process. Like many trans individuals, the partner was mostly elated and relieved to be finally bringing their self-presentation into alignment with their interior self: to no longer be living a dissonant life. To my friend, whose emotions were much more ambivalent, it often felt like there was no safe or sanctioned place to process their complexity of feeling. With economic barriers to therapy and other social supports often prohibitively high, books like

Transitions of the Heart (written by parents of trans and gender-nonconforming children) can help mitigate what could otherwise be intense isolation.

My Brother, My Sister could have been an addition to this small but growing literary offerings. In my estimation, it was not.

Let's begin with the most basic trap of all, the way the memoir's narrative is structured around and saturated in the physical aspects of transition, most particularly fixated on gender confirmation surgery and Haskell's assessment of how well or appropriately she believes her sister is presenting as a woman. While acknowledging that authors sometimes have little control over book jacket design, the plain red cover with a youthful photograph of Ellen "before" and a current "after" photograph invites the reader to center Ellen's appearance and physical transition rather than Haskell's experience as the cisgendered sister having to assimilate her sibling's late-in-life changes. A set of photographs at the center of the volume likewise foreground the "before" and "after" images.

As authors like Julia Serano and S. Bear Bergman have pointed out, the narrative of "passing" places the onus on a trans person to conform

to the world's high expectations of gendered behavior rather than demanding that the world

accept a person's self identification regardless of presentation. A trans person -- just like any of us -- may be a butch or lipstick lesbian, a twink or a jock, a sorority girl or tomboy. Bodies come in all shapes and sizes, and sartorial taste ranges across a field of more-gendered and less-gendered style choices. Historically, we (the public) have required a high level of stereotypical gender performance from trans women -- at the same time as we (feminists) blame trans people for perpetuating sexism through that same exploration of femininity.** Haskell perpetuates this scrutiny by making physical transformation the benchmark of transition, and by dwelling on the surgeries, the clothing choices, the gender-coded vocal and physical mannerisms, and other aspects of her sister's self-presentation.

While her sister's pleasures and anxieties around offering up her newly-visible self to the world are understandably preoccupying, Haskell's perspective is more often one of harsh judgment than it is attempt to follow where her sister leads. She frets that her sister will be unattractive, considers her clothing choices to slutty, and considers anyone who can't or is unwilling to fit into her neat categories of gender to be somehow at fault. For example, she writes of a trans woman her sister knows, "One man, though convinced he's a she, refuses to do anything to alter his rough male appearance" (158). As if this "refusal" to care about her appearance somehow invalidates the woman's self-articulated gender identity. She also offers unsolicited opinions on the femininity of other high-profile trans women:

From photographs, Jennifer [Finney Boylan], being younger and more typically feminine, seems to have made an attractive looking female, while [Jan] Morris by most accounts, before settling into dignified-dowdy, went through a grotesquely awkward wannabe-girl period (122).

I scribbled in the margins “seriously. out. of. line.

judgy.”

When Ellen visits Haskell after a period of cloistered transformation, Haskell nervously invites friends over and then grills them afterward on Ellen's ability to perform femininity: "The verdict ... she's very convincing. I said the hair's too blond, and Lily and Patty agree, the hair is too blond, but they're surprised at how good she looks" (146).

I think possibly a large part of my irritation is that I couldn't find Molly Haskell very likable, as a sister or as a feminist. She's critical of other women's appearances, ageist towards both the old (women who might be unable to catch a man) and the young (who are too slutty in appearance and too casual about identity), and hews close to gender expectations. One of her first reactions to her sister's coming out as trans is to fear that the tech- and number-savvy brother she relied on will no longer be good at computer repair or math. While she sidles up to the notion that this first reaction was unfounded, she never demonstrates for her readers that she has since come to revise her binary thinking when it comes to girl brains and boy brains.

At what might be a low point of the book, she even suggests that

Brandon Teena, the trans man who was the subject of the biopic

Boys Don’t Cry somehow “asked for it” by dressing in clothing appropriate to his gender and not disclosing his trans status:

Yes, the yahoos were uptight and murderous, but she in some sense invited the violence by taunting their manhood, pulling the wool over their eyes, and acting in bad faith (106).

Yes, she willfully mis-genders him. To fall back on the trope of the deceptive transsexual (

who supposedly invites violence through the act of passing) in a throwaway comment, in a book pitching itself as one about understanding trans lives, seems to me a fairly basic mis-step that, again, both Ms. Haskell and her editor should have caught before the manuscript went to press. That they did not suggests neither understood how problematic it was.

Which in turn calls the entire project into question, at least as far as its worth as a positive contribution to trans literature goes.

At the end of the day, I am glad that Molly and her sister have remained in good relationship, and I am glad that Molly gained more understanding of trans experience and trans history than she had when her sister first came out to Molly and her husband. I imagine that, at the end of the day, there are far worse reactions to have had from one’s family upon coming out trans (see:

transgender remembrance day). Yet I also wish that Haskell had let her own learning process cook a bit longer before publishing a book on the subject. As it stands,

My Brother, My Sister is a tepid-at-best, damaging-at-worst popular memoir that does little to invite a more complex understanding of trans people or sex and gender identity more broadly. I expected better from a self-identified feminist author, although I’m sure trans feminists

would laugh at my (cis-privileged) wishful thinking.

For those interested in learning more about trans lives, I would recommend

The Lives of Transgender People by Genny Beemyn and Susan Rankin,

Whipping Girl by Julia Serano -- who has also just published

a book on trans-inclusive feminism that I can't wait to get my hands on -- and also Anne Fausto-Sterling's excellent

Sexing the Body.

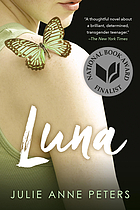

Luna, a young adult novel by Julie Ann Peters, is also an intimate fictional portrait of a sister coming to terms with her siblings trans identity.

*Cis or cissexual refers to individuals whose gender assigned at birth (usually based on external sex characteristics) matches their internal sense of their own physiological sex and gender identity.

**Trans men have, historically, had a very different socio-political experience within both mainstream culture (where they are often rendered invisible) and mainstream feminism (where they are more often embraced while trans women are actively marginalized).