To interrupt the recent run of photo and video and cat related posts with something a bit more library-professional about the place, I've been thinking a lot this week about the tendency of many historians, both amateur and professional, to undervalue their intellectual labor.

Amateur writers do this by, well, framing their labor as "a labor of love": something they've undertaken in their own time, funded out of their own (often shallow) pockets, because of their passion for a particular historical story and their desire to share it with the world. Professional academics do this by, well, framing their work within the context of their academic careers: emphasizing the often grim realities of contracting faculty salaries, vanishing funding in the humanities, and the "non-profit" (at least for the author) structure of most academic publishing.

Amateur writers do this by, well, framing their labor as "a labor of love": something they've undertaken in their own time, funded out of their own (often shallow) pockets, because of their passion for a particular historical story and their desire to share it with the world. Professional academics do this by, well, framing their work within the context of their academic careers: emphasizing the often grim realities of contracting faculty salaries, vanishing funding in the humanities, and the "non-profit" (at least for the author) structure of most academic publishing.

Neither of these frames are factually incorrect. We are often underpaid professionals who continue to do the work we're qualified to do out of personal passion and a belief that what we research and share with the world matters in some "greater good" sort of way.

Yet practically, this attitude toward our own work erases the necessity of, well, paying rent. It also colludes with a culture that equates cost with value to erase the work that goes into our creations. By romanticizing the historian (or any other intellectual or artist) who labors with little expectation of financial solvency, let alone reward, we contribute to a culture that devalues what we do. A culture that allows the institutions that employ many of us to pay wages that leave us perpetually financially insecure.

I have a couple of good blog posts on this subject -- by people more eloquent than I -- that I'd like to share, but first let me describe the situation that sparked these reflections.

As Reference Librarian at the Massachusetts Historical Society, one of my primary responsibilities is facilitating all of the requests for images of material in our collections for use in publications and other projects like documentary films, exhibitions, websites, and so forth. It's one of my favorite parts of the job: it allows me to stay in touch with what use people are making of the resources we make available, and increasingly means (as I pass the six-year mark!) that I see researchers whom I worked with at the beginning of their project finally completing their PhDs or winning a book contract or having an article accepted for publication.

|

| (via Massachusetts Historical Society) |

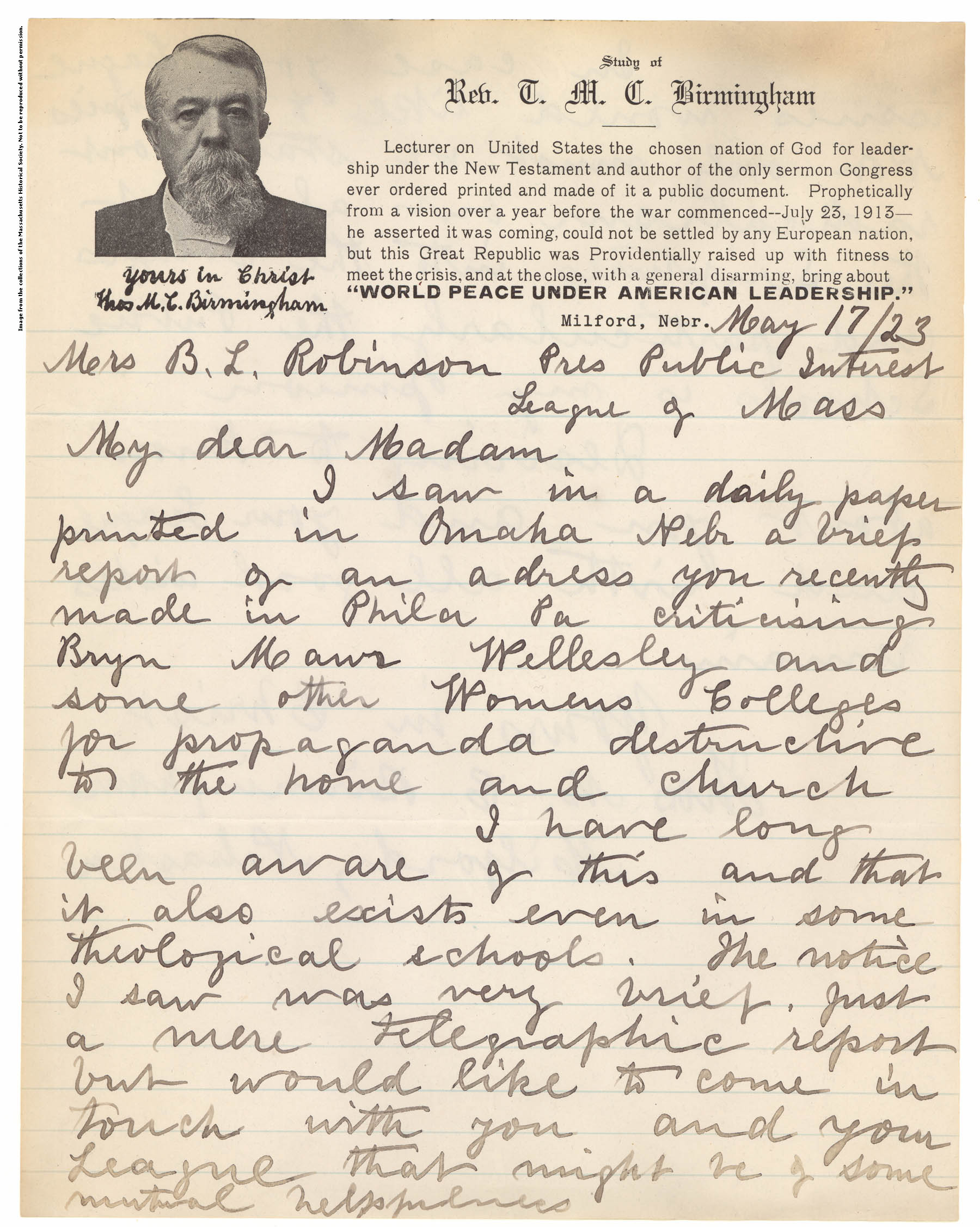

Images you can pull off our website, are available to re-purpose in certain exempt contexts -- classroom lecture, conference presentation, personal blog -- free of charge. The image above is a letter I wrote about for our February 2011 object of the month series.

For made-to-order high resolution images (the file type most professional projects require) incur fees. We charge for this service along two scales. There are reproduction fees, which cover the cost of the labor in producing the image; people are required to pay this fee regardless of how they are using the image -- even if they're just going to hang it on their bedroom wall. Then there are licensing fees, which are charged based on the nature of the publication; we license the images we create that people go on use in their own creations as a way to earn some income from our own creations (the digital reproductions of material in our collections) and pay not only staff salaries, but also for the ongoing care and keeping of these valuable historical documents and artifacts.

This can be expensive. Images cost $45-60 per file in reproduction fees, and anywhere from $0-450.00 per image in licensing fees. If you are an author seeking to use multiple images in your forthcoming book this can add up fast. I've worked with several authors in the past year who, despite small academic press print runs, have faced over $1,000 as a quote for obtaining the images they would ideally like to use. Our fees are steeper than some independent research libraries charge, but also more sensitive to the scale of individual projects than others. In short, we're balancing the desire to provide access with the need to pay our staff for the work that they do and all of the not-inconsiderable overhead of preservation, storage, and security.

While most people understand this, I do have the occasional individual who tries to haggle with me to get the prices reduced or eliminated. They cite a series of potentially mitigating factors: their relationship with the Society, the fact that they're paying out of pocket for the images, the fact that they're retirees on fixed incomes, that they're academics on tight incomes, that other institutions have offered them lower rates or waived the fees, that the author will not be making only -- sometimes, in fact, they're losing money -- on this project, and so forth.

I'm sympathetic. I really am. I also understand completely when people decide they can't afford our prices and seek cheaper images elsewhere -- I likely would in their shoes if the cost was prohibitively high. I wish them the best and honestly mean every word that I type.

But having had several exchanges along similar lines in the past few weeks, I've been wishing I could have slightly more meta conversations with some of these people. "If you've spent ten years writing and researching this book on your own dime," I was to ask them, "why for all that you hold holy have you signed a contract with a for-profit press that is requiring you to pay upfront for all of the production costs?"

Or, sometimes, when they get sniffy about how steep our fees are, I want to lean a little heavier on the words labor and staff time in my replies. "Why," I want to ask them, "do you feel entitled to obtain something from us for free, even after I explain to you that creating this product takes the time and effort of half a dozen people who work at our library?"

In these exchanges, I sometimes see an altruistic competitiveness creep in that's really unattractive: I've labored over this work for years without complaint, expecting little reward, some people seem to imply (likely not consciously), and because I'm not benefiting financially from this project -- in fact, I'm losing money! -- you should be likewise generous to the cause of History and give these images to the project for free.

Sometimes, there's even the implication that we're somehow holding these digital photographs hostage, selfish money-grubbing institution that we are.

The librarian part of my soul certainly kens this argument. If our society was structured differently, with robust socialized funding for cultural heritage institutions and a guaranteed national income for all citizens that provided me and my family (and everyone!) with food security, housing security, and healthcare, then I would absolutely advocate we digitize and make freely available the images our scholars want to use. They are smart, articulate, energetic, diligent, and prolific people -- and the wide range of stories they come up with to tell using the rich materials in our collections are part of what make my job a daily joy.

But we don't currently live in that world, and in the world we do live in we should not undervalue our own already culturally devalued work by setting ourselves up pre-emptively as martyrs.

Think carefully before you give your work away, particularly to others who will make a profit from it.

Even if you decide to give your own work away, recognize that this does not give you the right to expect others to provide you goods and services for free. Factor in that even on projects you are doing for the pleasure of the work, you will need to pay people fairly for the work they contribute.

Sometimes people will charge what you feel is too much for their labor or products. It's certainly fair to decline their goods and services and go elsewhere. If they care about keeping your business, or if too many people decline what they offer because the price is too steep, they will probably decide to lower their prices.

What you should never do is try to shame or guilt scholars or artists for earning a living doing the work that they love.

You also shouldn't be ashamed or feel guilty for trying to earn a living doing the work that you love.

One of the best pieces of advice I ever got as an early professional was to be sure to not undervalue my work, and to charge an hourly rate for free-lance research that, at the time, seemed scandalously high to me (used, as I was, to student stipends). But the higher hourly fee we negotiated demanded that both my employer and myself take the project seriously as a professional endeavor. In the two years since then, I have given several colleagues who asked me for free-lance advice the same nudge: "Ask for what you feel would make the job worthwhile," I tell them. Or, "Think about what you believe your time is worth, and then ask for a third again more."

I also remind them to calculate in any expenses they may incur on their way to completing the job they're being asked to do: transportation, equipment, service fees, etc.

One of the best pieces of advice I ever got as an early professional was to be sure to not undervalue my work, and to charge an hourly rate for free-lance research that, at the time, seemed scandalously high to me (used, as I was, to student stipends). But the higher hourly fee we negotiated demanded that both my employer and myself take the project seriously as a professional endeavor. In the two years since then, I have given several colleagues who asked me for free-lance advice the same nudge: "Ask for what you feel would make the job worthwhile," I tell them. Or, "Think about what you believe your time is worth, and then ask for a third again more."

I also remind them to calculate in any expenses they may incur on their way to completing the job they're being asked to do: transportation, equipment, service fees, etc.

My current free-lance rate starts at $25.00/hour, exclusive of expenses, though I do negotiate based on the nature of the project. I always advise emerging professionals who ask what to charge that they should never accept less than $15.00/hour for their research or scholarly work.

I promised you links.

Writer John Scalzi has an excellent round-up of posts he wrote about how to spot an exploitative book contract (and why he would never sign one). If you read only one of the posts, I would recommend "New Writers, eBook Publishers, and the Power to Negotiate":

People: Unless the publisher you’re talking to is a complete scam operation, devoted only to sucking money from you for “publishing services,” then the reason that they are interested in your novel is because someone at the publisher looked at it and said, hey, this is good. I can make money off of this. Which means — surprise! Your work has value to the publisher. Which means you have leverage with the publisher.And on a more academic note, Sarah Kendzior asks at the Chronicle of Higher Education, "Should Academics Write for Free?"

Academics entering the media world tend to move from one exploitative arena (low-wage academic work) to another (unpaid freelance writing). But writing must never be an act of charity to a corporation. Ask for what you are worth—and do not accept that you are worth nothing. Insisting on payment for your labor is not a sign of entitlement. It is a right to which you are entitled.We all labor for free, at times. I've been writing this blog on an unpaid, voluntary basis for over six years; I won't be stopping any time soon. Yet I've just spent three hours writing this post. That's $75.00 I owe myself. I also write book reviews, for free (or in exchange for a book). This fall I'm working on a series of seriously under-paid encyclopedia articles, which I chose to take on for the experience. I will probably negotiate for better terms next time, or decline the next call for authors that comes my way.

There is nothing intrinsically bad about voluntarism. But it does not follow, therefore, that there is something intrinsically virtuous about volunteering your time (or asking another person or institution to volunteer their labor and resources) rather than asking for recompense.

Think carefully about how, why, for whom, and on what terms you will labor for free.

And respect the right of others to determine for themselves how, why, for whom, and on what terms they will do the same.

No comments:

Post a Comment