Acceptance and self-acceptance amidst the anonymity of cities like New York and Los Angeles and even Boston meant little, I was convinced. One had to travel beyond the large metropolitan areas on the two coasts to places where diversity was less acceptable, where it was harder to melt into the crowd ... that was where the majority of gay people lived anyway, even if you didn't read about them in the gay press or see them on the evening news (In Search of Gay America, 11).What Miller found in his travels was that queer people in the heartland were often less visible than their East and West coast counterparts; they kept their heads down and their mouths shut, maybe living in a community where everyone knew they were gay but no one openly acknowledged it. Many of Miller’s interviewees talked about the social isolation, particularly if they were un-partnered; in the pre-internet era single lesbians and gay men often had to travel regularly to urban centers to meet and socialize with others like themselves.

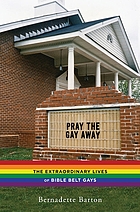

In the two decades since Miller's travels, much has changed in the world of LGBT visibility, culture, and activism -- yet our collective understanding of queer culture remains focused on urban, coastal areas as gay-friendly, while the rest of the country is dismissed (especially by those who don't live there) as a place where "diversity is less acceptable" and life is harder for queer men and women trying to make their way in the world. Bernadette Barton's new study, Pray the Gay Away: The Extraordinary Lives of Bible Belt Gays (New York University Press, October 2012) both confirms and complicates this narrative.

A Massachusetts-born academic who moved with her partner to Kentucky, Barton was taken aback when a neighbor denounced homosexuality as a sin after Barton came out to him. Curious to understand how "Bible Belt gays" experienced this climate of casual anti-gay sentiment, she began interviewing gays and lesbians who grew up in what she terms the "Bible Belt panopticon," the southern mid section of the nation in which tight-knit communities and strong evangelical, fundamentalist Christian culture come together to create and police conservative norms. When the normative culture is implicitly anti-gay, open bigotry is not needed to encourage self-policing. For example, Barton quotes an interviewee reacting to a church billboard proclaiming, "Get Right or Get Left":

Get right means to be saved and get left means to be left behind at the Resurrection, but this also conveys the dual message of the church's political affiliation as well. It's very polarizing, and when I read it, it sounds like a threat.Barton observes:

This is an example of how antigay rhetoric, especially to a Bible Belt gay, doesn't have to say anything at all about homosexuality. It's the associations. A Bible Belt gay knows homosexuality isn't included in the right column.Pray the Gay Away explores different ways in which this Bible Belt panopticon manifests, from family expectations to ex-gay ministries, gay-unfriendly workplaces and legislation to ban same-sex marriage. Throughout, the voices of Barton’s interviewees are powerful evidence in support of her thesis. One graduate student, for example, tells Barton about how his parents tried exorcism when they found out he was in a same-sex relationship. When he remained unrepentant they not only disowned him and cut all financial support, but also removed all of his belongings from his dorm room before they returned home. Through the support of his campus community, the student was able to remain in school -- but the resilience of the child does nothing to redeem the horrific behavior of his parents.

I grew up in West Michigan, an area that is -- though technically outside the Bible Belt proper -- incredibly religiously and politically conservative. Reading Barton's work, I found much to identify with in its descriptions of life in a community that resists difference and where anti-gay feeling is commonplace. I was particularly struck by her observation that in such communities, "gay" and "straight" are the only two categories a person can belong to. Anyone who is something other than straight is “gay.” You're either "right," after all, or "left." That observation made me wonder whether it took me so long to recognize my own sexual fluidity in part because I literally had no language with which to describe myself.

Though I no longer have to live in a culture that makes it difficult (if not dangerous) to speak of my existence, I am mindful that what Barton terms the “toxic closet” effects everyone whom anti-gay bigotry touches, not just queer folk. My parents, for example, felt profoundly alienated when the city council rejected an anti-discrimination ordinance last year. And my grandmother is uncertain with whom she can safely share the joyful news of my marriage. The “Bible Belt panopticon” constrains us all.

At times, Pray the Gay Away seems to paint the Bible Belt as a monolithic culture of hate. I was pleased to see how careful Barton is to point out that she "deliberately sought out individuals who grew up in homophobic families and churches to best explore their consequences," and that her narrative describes the normative culture of the Bible Belt, rather than attempting to describe all people therein. (For a broader examination of queer folks' relationships with their families of origin, see the excellent Not in This Family by Heather Murray.) Barton’s conversations with gay Christians and gay-friendly church leaders, as well as her nuanced exploration of ex-gay ministries help show that even situations which appear toxic at first glance often contain more complex realities.

Yet ultimately, Barton argues that in the Bible Belt region "rampant expressions of institutional and generalized homophobic hate speech in the region bolster individually held homophobic attitudes and encourage those who have dissenting opinions to remain silent." One lesbian student whom she interviews theorizes that it might even be accurate to identify these anti-gay attitudes and actions as "gay cultural genocide.”

I highly recommend Pray the Gay Away to anyone with an interest in contemporary queer experience, in Bible Belt Christianity, and the intersection of the two. I’d go so far as to say it’s required reading for anyone who cares about what it means to be gay in America today. Whether or not you’ve ever lived in the “toxic closet” yourself, too many of our fellow citizens still wake up there every morning. We owe it to them to listen to the stories they have so generously shared.

Cross-posted at In Our Words.

No comments:

Post a Comment